Really Good Tomatoes asks irreverent questions and offers hopeful answers. It’s a newsletter about culture, behaviour, food, art, relationships, pleasure, politics, work, environment, identity, and society. For people who refuse to be fobbed off with crap tomatoes.

In September 2022, I posted a picture of my pudding on Instagram. “Most days I spend the baby’s nap time sitting on the sofa, dead-eyed and scrolling my phone,” I wrote. But *some* days I make apple crumble.” Accompanying it was a picture of said crumble, topped with crispy oats, cream drizzled over the buttery crumb.

My daughter was four months old at the time. The book I’d ghost-written had just been published and so, a week earlier, I’d hauled my postpartum body into a tight skirt and heels in order to attend the launch party. There were dick-shaped waffles and a chocolate fountain. It was 122 days since I’d last slept for more than two hours in a row. Standing at my kitchen counter eating apple crumble, I felt a tugging sensation in my diaphragm. Somewhere between grief and hope. If only life could be this simple all the time.

Like most liberal women, I’ve watched the tradwife trend unfold with a mix of horror and “couldn’t be me” dismissal. When I read The Times interview with Hannah Neeleman aka Ballerina Farm last summer, there wasn’t a single detail I felt I could relate to. Mostly, I observed it as nonsense. Maybe there was a whiff of feminist backlash in there, a regressive undercurrent, but ultimately they were just housewives and stay-at-home mothers. People like this had always existed in society, only now they had Tik Tok accounts.

It’s important to acknowledge that there isn’t actually a unified theory of tradwifery (pronounce it like midwifery). And there isn’t a single type of tradwife. It is not, for example, necessary to live on a farm. You can also have a glossy white kitchen or a city-centre duplex. You can dress in head-to-toe gingham, do yourself up in a 1950s pastiche, make dessert while wearing couture, or you can just wear jeans.

It’s not really a movement, though it has been described as such. It is at best a hashtag. As far as I can tell, anyone who does any kind of domestic work (what Marx called reproductive labour) on camera can call themselves a tradwife, or be designated one, even if, like 22-year-old Nara Smith, they actually have a full-time modelling career. To be fair, Smith has never described herself as a tradwife, and the only trad-adjacent thing about her is that she married Mormon model Lucky Blue Smith and had children in her early 20s. She isn’t even the primary caregiver.

“Every night before bed, Lucky and Nara review their upcoming work obligations and map out a childcare plan for the next day,” Carrie Battan, who interviewed the couple for GQ, wrote in 2024. “Often they will divide and conquer, with each parent taking the kids for half the day and working the other half.”

Honestly this sounds more equitable than my marriage. No, when we hear the term “tradwife” what we think of is someone more like Kelly Havens Stickle, in her rural Ohio home with her pre-Raphaelite hair and a wardrobe that looks like a mashup of Toast and Gudrun Sjödén (but is almost certainly home-made), homeschooling her kids, making patchwork quilts, and posting bits of scripture alongside photos of herself looking blissed out while holding a toddler in dappled winter sunlight.

Or, we think of someone like Gwen Swinarton, aka Gwen The Milkmaid, floating round her pristine kitchen in ditsy florals, baking “pretty cakes” for her “masculine cowboy,” her perfectly-coiffed blonde hair cascading in ringlets down her back.

“These joyful housewives seem to enthrall and repel us, nauseate and fascinate us,” wrote Amy X Wang in the New York Times in 2024. “Appalled onlookers deride them as thorns in the side of feminist progress: chauvinism incarnate, sexism made glamorous, proselytizers of a harmful fantasy.”

I probably wouldn’t go that far, I thought to myself. They’re just people making content on the internet. But for a long time I just didn’t get involved in the conversation. Why would I? None of this had anything to do with me.

Me? I’d rather spend my energy teaching myself to darn, researching which plants to grow in order to cultivate a dye garden, and perfecting the salt-to–cabbage ratio in my homemade sauerkraut.

I’ve always been good at DIY, a term I use to mean everything from visualising and then making my own curtains, to putting up the poles on which to hang them. I was hammering nails into the wall the day before my daughter was born, and I spent around six months worth of naptimes stitching a quilted wall-hanging for her bedroom (I’d never done applique or quilting before but compared to the first year of parenting, I reasoned, how hard could it be?).

I discovered something else on maternity leave: I really like myself when I’m engaged in tangible tasks. I really enjoy being this version of me. The times when I’m cooking, or sewing, or doing DIY around the house, are the times I feel most present and chilled out. I don’t even mind laundry. Where some are ground down by its neverending quality, I find the repetition of it, the rhythm and flow, to be calming.

The stress and resentment of cooking, cleaning, tidying, putting on a wash, attending to life admin, does not arise because the work itself is stressful. It is because I have to do it around the edges. I have to do it in my free time which, given the 24/7 nature of small children, isn’t much. No wonder I have stood in my kitchen, head throbbing with the overwhelm of juggling work and domestic life, and wondered what it would be like to just pick one. A popular refrain among working parents is that we feel like we’re doing everything, badly. Wouldn’t it be nice to just do some of it, well? Since I returned to work after maternity leave, I regularly find myself running dejectedly through the mountain of tasks, both tangible and administrative, requiring my attention and longing for an empty schedule in which I could actually get things done.

It is a fantasy, of course. Not least because it’s impossible to actually get anything done with a toddler running around, and looking after the kids is a pretty non-negotiable part of the deal, both financially, and ideologically. Still, I had dismissed tradwifery as irrelevant even as I acknowledged to myself that I some of my clearest moments of peace and accomplishment came while I was doing things that could reasonably be termed “homemaking”.

About a year ago, artist and writer Kaitlin Prest shared a post on Instagram in which she reframed tidying a drawer full of junk as a creative process. “One of the things I realised is restorative for me,” she wrote, “Creativity that is functional and for an audience of only one: Me. aka home improvement projects. aka ‘cleaning.’ lol.”

Something clicked for me when I read this. To reclaim these chores, this work, as creativity felt like an important shift in mindset. Slowly, I began to consider tradwifery through a new lens. I didn’t recognise myself in any of these influencers, and I sure as hell wasn’t about to start calling my husband a “masculine cowboy,” but perhaps there was a version of the story that could work for me. Maybe there was a world in which it could align with my principles. Because actually, when you think about it, living off the land, cooking everything from scratch, making your own clothes, and being able to raise your kids without losing yourself in the insane juggle of work/childcare sounds quite nice? It sounds quite radical, even. As discussed recently on the

podcast, there are elements of the tradwife existence which overlap with anarchist ideas.Even in more mainstream conversations, when we talk about the parts of capitalism we wish we could escape, and the things we wish we had more of in our lives, the list can read a lot like a tradwife manifesto. “Yes to community. Yes to mutual aid [...] Yes to making delicious food out of things that grew in the earth, and to making whatever kind of art makes me happy,” writes Emily McDowell in in an essay entitled I’m not fucking around any more. “Yes to buying less shit I don’t need. Yes to joy and laughter and not tracking in real time every terrible thing happening everywhere. Yes to work and activities that feel good in my body and bring me peace. Yes to stillness. Yes to trees and meadows and oceans and the sky. Yes to love.”

Indeed. I too would love to be spending more time exploring the outdoors with my kids, or coming up with fun craft projects for them. I would love to be able to cut down on my material consumption, making and mending, recycling and repurposing. I would love to be cooking delicious from-scratch nutrient-rich meals for myself and my kids every day. The reason I’m not is not because I’m defying patriarchy but because I don’t have the goddamn time. Who does?

Like Prest, one of the reasons I started to think differently about homemaking was because I was exhausted. I was burnt out from trying to stay on top of everything at work and stay on top of everything that needed doing at home. And I am very far from being the only one. It is precisely this realisation that many believe has sent women flocking to the tradwife lifestyle. In the post Lean-In era, women have realised that, in the words of Megan Agnew, who wrote the Ballerina Farm story, “individualistic feminism didn’t resolve anything unless you were a millionaire. For normal working mothers the girl-boss era achieved virtually nothing.”

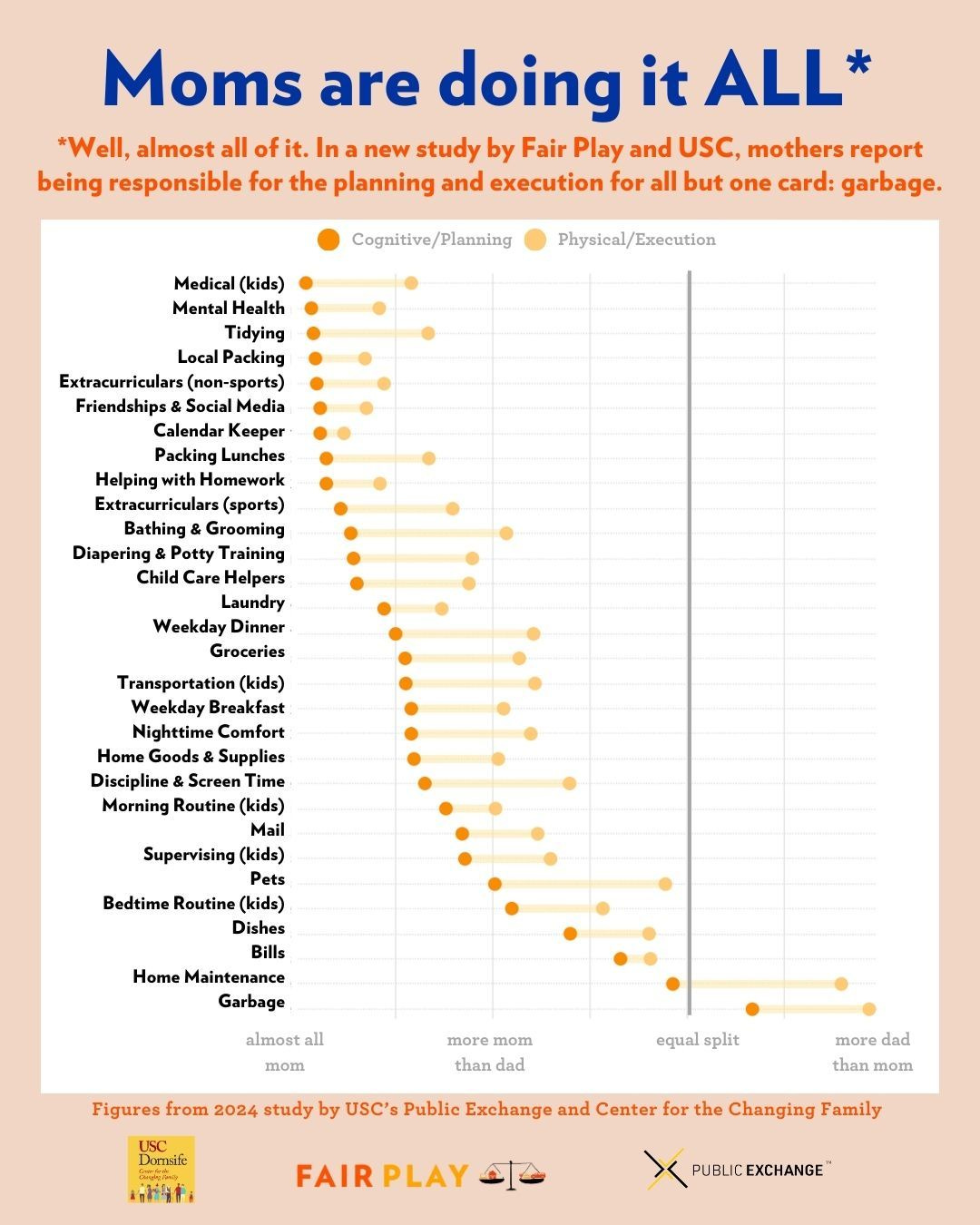

Because no matter how many hours women work, they still shoulder the bulk of the domestic workload. Even couples who believe they have an even split, are shown time and time again to be unequal, particularly when things like kin work are factored in.

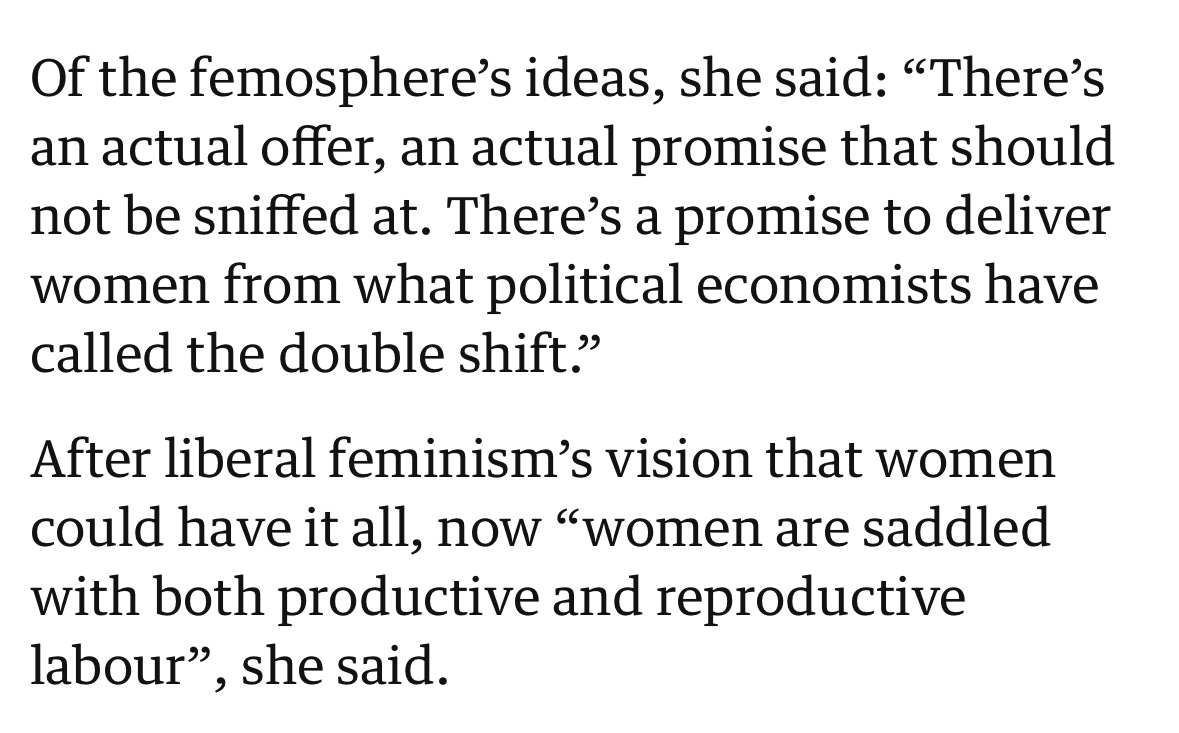

This idea was echoed in a recent exploration of the “femosphere, in The Observer. The femosphere is defined as the online space occupied by women with conservative values, gender-essentialist views, and weird dating tactics. It shares a lot of its beliefs around sex and relationships with the “manosphere” (the misogynist internet world inhabited and influenced by the likes of Andrew Tate) but with one key difference: Most of the women who align themselves with it explicitly call themselves feminists. Huh!

How can rejecting work and financial independence in favour of being a kept woman be feminist? You may well wonder. There are those who would argue that anything a woman chooses to do is feminist as long as it was her choice. I don’t subscribe to this. But I do think intentionally opting out of bad systems can be a radical act.

I know a bit about bad systems because I work freelance in the UK media. I have 15 years of experience and by all accounts am very good at what I do and yet I do not feel like I exercise much control over my career. I still struggle to find work. I still struggle to convince people to pay me properly for my work. In the domestic realm I may not get paid either, but I am in control. I decide what matters, where to channel my energy, and I enjoy immediate tangible results. My work is appreciated, both by me, who gets to enjoy it as an occupant of the domestic space in question, and by my family, friends, and community for whom I do it, and with whom I share it directly.

Of course, anyone who’s actually cooked for kids knows they’re just as likely to reject it out of hand as they are to gobble it up and ask for seconds. It’s total pot luck and it’s both maddening and dispiriting in equal measure. But let’s not get hung up on that. Like I say, this is a fantasy.

Is now a good time to remind you that Really Good Tomatoes is a reader-supported newsletter? So if you’re enjoying it, it would be super cool if you thought about upgrading to a paid subscription.

It costs £4/month or £40/year. Paid subscribers also have access to the entire back catalogue of paywalled articles.

As feminist theorist Dr Sophie Lewis says in the Observer piece, “The so-called trad life is genuinely seductive to women who rightly hate the endless grind [...] that’s something that liberal feminism needs to recognise it hasn’t provided a solution to.”

And so, because cultural discourse is fated to go round and round and round, I find myself standing on the edges of a very well-worn feminist argument: Why do we consider domestic work a less valuable occupation? Why do we disparage the people who choose to focus on it? Shouldn’t we be applauding and rewarding it? Shouldn’t there be a universal basic income?

(Interestingly, as this article points out, “19th-century homesteading, the source of so much inspiration for both tradwives and the GOP – was not a private endeavor undertaken by hardy men and their supportive wives. It was the result of the huge government subsidy program known as the Homestead Act.”)

Of course, I don’t think most tradwives are consciously trying to defy capitalism, or subvert social order. I don’t think what they’re doing is particularly feminist or anarchic. At the end of the day, they’re influencers. Some are creating genuinely innovative and intriguing content. Some are clearly grifters. Some are trying to spread the word of God. And some are just living their lives. Or performing a version of their lives, however you want to look at it.

And, of course, I don’t really want to be one. But I think it’s worth paying attention to the fact that, for many of us, the way we are trying to live feels overwhelming. And that there can be meaning and replenishment in functional, everyday creativity. To profess sympathy for, even alignment with, the tradwife idea feels incongruous but it also feels important to examine. There has to be room to say, actually, I would like to give more time and attention to the domestic tasks and activities in my life. And I would like those tasks and activities to be recognised as socially valuable.

At the very least, I would like to be able acknowledge them to myself as a form of creativity, care, and cultural participation.

Welcome to the subscriber-only section of the newsletter where I share what’s going on in *my* life right now, as well as my

🍅 Tomatoes Of The Week 🍅

(Links, recommendations, anecdotes, funny observations and various other bits).

Send me yours! Subscribers can comment below, reply directly to this email, or join me in the Friday lunch time chat.

I was really intrigued by this piece in GQ on how male lust has found its way back into fiction. I confess I hadn’t really noticed the absence of what the author calls “unvarnished male desire” from fiction over the last 5-10 years, something the writer puts down to “post-MeToo reluctance” but now that it’s been pointed out to me, I see it. I have, however, read a LOT of unvarnished, complicated, and occasionally disturbing female desire in that time, for better (Milk Fed, Boy Parts, Three Women) or worse (Luster, Butter, All Fours - there I said it!). So maybe it’s time the boys had a go, and I’ll definitely be sticking some of the titles mentioned in this piece on my reading list.

In the meantime, what I’m *actually* currently reading is The Rabbit Hutch by Tess Gunty.

The new series of Severance. God, I love this show. It’s dark, it’s funny, it’s visually stunning. I loved how the ORTBO (Outdoor Retreat and Team Building Occurrence) episode took its sterile retro-futures creepiness to new and snowy levels but then in other moments looked like a mid-century epic.

I really enjoyed the below short video showing some of the colour palettes in the show. I’ve also been going down rabbit holes with fans’ colour theory about the show (blue = innie world, red = outie world, so purple = shit is about to go down!) and reading everything I can from the show’s design and set decoration team. Much joy!

I keep hearing that Y2K fashion is back but truly nothing has catapulted me back to Bar Med in Guildford c. 2002 more violently than these rhinestone bootcut jeans. Dear sweet lord, I can almost taste the cranberry Bacardi Breezer. Thanks, Reformation, for this blast from the sticky-carpeted past. I’m actually… almost… tempted? Course, they won’t be the same unless they reek of last night’s indoor cigarette smoke and some things simply can’t be recreated in 2025.

I absolutely love this one, thank you so much. I appreciate your trad wife thoughts.